V.I.P Treatment

| During his time in the Pacific and the Middle East, Don Mackenzie escorted troopships, surveyed the Malaysian peninsula and survived the Japanese bombing of Ceylon. After being redeployed to the European theatre, Don landed, what he believed to be a ‘really cushy number’ flying V.I.P’s. From these experiences it is clear that danger was an ever-present reality, even in such supporting roles, and Don wasn’t guaranteed immunity from the potential harm in the skies over Europe. | |

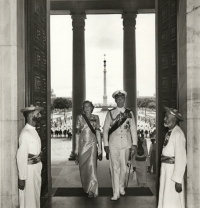

| The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) was established as an autonomous service of the New Zealand Defence force in 1937 and played an important role in the Pacific theatre during the Second World War. By the end of hostilities in 1945 more that 7000 Kiwis were stationed throughout the pacific serving in a variety of RNZAF squadrons that covered the full spectrum of air operations, support and ground protection. Don Mackenzie: Later on my ambition was to fly a Mosquito, and of all things … I got a signal from Delhi asking me would I go way the hell up in Burma to air test a Mosquito. A Mosquito plane, there had been a squad that had come out from England, had all been painted duck-egg blue, and they had an aerial survey of Indonesia, and one of them had crashed a plane at a place called Argatala and had damaged a wing, and they had fixed it up, and I got this signal, and I couldn’t get there quick enough to fly it, my one ambition was to fly that plane. Patrick: Why was that? Don Mackenzie: They were a lovely plane, twin-engine, made of wood, 2 Merlin engines, the engine similar to that in a spitfire and they were beautiful planes to fly and they were very very popular in England and the Middle East, bomber fighters they were, they were a beautiful plane. Anyway, Dick Bell, not the Dinger Bell I mentioned this is later. My navigator in Burma was a Welsh policeman actually, and he’d flown a lot with me, so I said to Dick "Dick, I’m gonna go up to Aggatala to fly this mosquito, do you wanna come?" He said "Yeah Mack" he said "I’d fly anywhere with you." So, we got a ride, we were flown up there, and we sat in this mosquito with no hand book and no dual control and luckily I did cope, and I flew the aeroplane, landed about 6 or 8 times there then I flew it back to Calcutta where I tested it, in theory for about 2 or 3 weeks, and by this time I was very sick of India. So Dick Bell and I decided we’d test this Mosquito aeroplane. We flew to Allahabad, this was 1500 miles, and buzzed the Air Headquarters, which was strictly out-of-order, though they knew who we were, and I was ordered back to Calcutta to go before a Court of Enquiry. A very decent Air Commodore was in charge, and he said "Oh, Mackenzie, what’s your trouble?" I said "Sir, I’ve been in the East too long, I want to get out of India." He said "Is that all your problem?" I said "Yes, I want to get to England." So he reprimanded me, which was of course the thing to do, and he said "I’ll have you on a boat to England in a month." In 6 weeks I was on a boat to England, so I achieved my objective in doing so. We called India the "Arsehole of the Empire" Patrick: Why England? What were you assigned to do once you arrived? Don Mackenzie: I applied to get on to Liberators. I had qualified to fly Liberators, Bombers, and 4 engines. I had only just qualified; I hadn’t flown them apart from that. Anyway I was given 6 weeks leave, because I had been overseas over 3 years, and then I got posted to 510 Squadron, which was the VIP Metropolitan Passenger Squadron, the only Squadron in the Royal Air Force that flew passengers. And that was one of the best postings you could get in the Royal Air Force. We were based at Hamden, right here in London, NW London, on the Tube Train, and we’d get 2 or 3 days off after doing a trip to the Continent or Middle East maybe. You could go into London or go away wherever you liked. And we got pretty sensible and reasonable leave, so we often got time off and we’d go around England. And that was solely flying passengers, and they were VIP’s. Patrick: Do you remember any of the passengers you flew? Don Mackenzie: Yes, one you might know. I flew several times on a Friday night, Lord Beaver-Brooke, he owned the Daily Express Newspaper. A hereditary title, a very wealthy man, he was on the War Council with Churchill and all the rest of them. And he lived near Bath, which isn’t very far from London. And he would on a Friday night, he would always arrive late, obviously quite understandable, he was a very busy man on the War Council, the top level … of the War really, and so he didn’t have much time to himself. So I flew him a couple of times only, near Bath, and had to get them back in the dark virtually to Hamden, a complete black out. So I had to get them back in very hazy weather very often, and land in pretty tough conditions, but however we got there. Yes, I flew, mainly Generals in all manor of positions. I flew the Prince of Monaco to Paris from London, Prince John of Monaco, the N.Z. High Commissioner, I flew him once – can’t think of his name. I’ve got it in that booklet, I’ve a list of a lot of the important ones, but we flew a lot of Army Majors and whatever, the main ones were Generals and those sort of people – I can’t think of their names. Patrick: Did you enjoy that? Were you satisfied? Don Mackenzie: Very cushy, very good treatment, always. Now the one trip that I will tell you about now is the one where I had to fly Lady Mountbatten. I had flown Lord Mountbatten in Burma, but I was very much one of the lower commands, very much so, he was Head Command. She was the Head of the British Red Cross, and in effect, in reality she should not have been in an Air Force plane, she should have been in a Red Cross Plane, but there were no such planes, they didn’t have any to spare. Anyway, Lady Mountbatten, I was detailed to take her to the German/Dutch border to four different temporary hospitals where it was right in the firing line, that area, very, very big battle took place, and that was where they had the biggest parachute landing of the war, at Arnhem, and they had these temporary hospitals and the aerodromes weren’t necessarily terribly close, we had to land at the nearest drome and then they’d go by car or whatever, for Lady Mountbatten to inspect the hospital. Anyway, we were stationed at Brussels for the week and things were very limited there. When flying from into France and Belgium, you flew in pretty narrow corridors, probably 20 miles wide; if you got off those you were in the danger area. So anyway we coped with that, and we got to Brussels and then 2 or 3 days I went to those different, those 4 hospitals, they didn’t have names, they just had numbers. She went to the hospitals and we stayed at the Aerodrome of course. And anyway, the next day we were detailed to take her to Eindhoven in Holland, which was quite a distance away. So, got briefed and set out for Eindhoven. I was detailed to take her to the German/Dutch border to four different temporary hospitals where it was right in the firing line, that area, very, very big battle took place, and that was where they had the biggest parachute landing of the war, at Arnham, and the British and the Yanks dropped 10,000 people and somewhere near 8,000 of them were either shot, killed or shot on the way down by the Germans, so there were terrific casualties, and they had these temporary hospitals and the aerodromes weren’t necessarily terribly close, we had to land at the nearest drome and then they’d go by car or whatever for Lady Mountbatten to inspect the hospital. Anyway we were staged in Brussels for the week and things were very limited there, flying from in…France and Belgium, you flew in pretty narrow corridors, probably 20 miles wide; if you got off those you were in the danger area. So, anyway, we coped with that, and we got to Brussels and then 2 or 3 days I went to the different, those 4 different hospitals, they didn’t have names, they just had numbers, and she went to the hospitals and we stayed at the aerodrome of course. And, anyway, the next day we were detailed to take her to Eindhoven in Holland which was quite a distance away, so got briefed and set out for Eindhoven. I was in the circuit at 1200 feet, undercarriage down, flaps down, going in to land, I had identified myself, which as it turned out didn’t mean a thing, and all of a sudden, my port engine blew up. And I thought – Oh, you know, it had happened, not many times thank goodness, where an engine packed up when you were flying, and I thought it was just a faulty engine. Next thing I was looking out as you do to trim tabs on the Ailerons, to fly on one engine, very tricky if you’re not careful. You can’t turn towards that side; you’ve got to turn away on the dead engine. Anyway, I was looking out and they blew a hole in my Aileron and then I knew I was being hit by enemy fire, and cutting a long story short, what happened was, the Germans had taken the Aerodrome overnight and I was the first person to land on it. Patrick: What year was this? Don Mackenzie: 1944, October 1944. And the Germans had progressed overnight, there were two aerodromes within Eindhoven, and they’d taken one that I was going in to land on. And anyway, there were 17 hits on the aeroplane, nobody was badly hurt luckily. By a miracle, it was only 1200 feet I got out of their fire and headed back for Brussels where I hoped to get to. I got about 20 or 30 miles back and realised I wasn’t going to get to Brussels because I was losing height, only one engine, flaps down, undercarriage down, 17 gapping holes in the plane, which is very bad aerodynamically, and I was loosing height and I had to land. There were no aerodromes, and I didn’t know what the hell to do. You think of a lot of things in those times, and I thought" oh well, I’m going to have to belly land, lift the undercarriage and flaps and land on the belly". And I went to do that, but unfortunately they had shot my hydraulics out and I couldn’t do it. So I had no option but to land. I landed successfully, and I got a citation and an Air Force Cross for that flight. Though in actual fact, in India, I had been recommended for an Air Force Cross that never came about. We used to call ourselves the forgotten Army and Air Force in India and so I never got that. But I did get one in the end which was quite an honour. Patrick: Why were you recommended for one in India? Don Mackenzie: Because I had done a lot. I was no different from anybody else. You are doing a job which maybe you don’t want to do, I was terribly lucky, I was told what to do, or I would have gone to England and very likely have been killed on bombing. I went the easy way that I mentioned, to Singapore, Ceylon, India, Burma, England. And in the meantime, my mates were getting killed too often, and so therefore I was very lucky that I went the way I did. It’s fate. I mean, it wasn’t good flying, my part of it, it was mainly good luck. The things I got out of, where I could of so easily have been killed. So, yes, that would have been the biggest On leaving a squadron or unit one had to be given an assessment of his ability as a pilot. The classifications were: Below average Average Above average Exceptional All of Dons flying assessments were above average with three exceptions. He was assessed (in his log book) is “exceptional.” In total Don flew 55 different types of air craft and approx 2300 hours, 1100 of these were flown over the Indian Ocean in a single engine aircraft. Don: “On the other hand I was no different to every one else - I was just doing the job I was detailed”. |