Times Produce Events and Events Produce the Men.

| Stuart Hayton of Taranaki was like many New Zealanders wanting to join the army during the Second World War. He was very determined to get overseas; showing what lengths Kiwis would go to. As a member of the eleventh reinforcements Stuart saw service in Italy joining the 21st battalion going into action shortly after Cassino. Stuart Hayton wasn’t just an infantryman; he also served as an intelligence officer and was involved in the sensitive issue of Kiwi soldiers marrying Italian women. | |

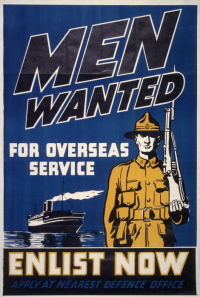

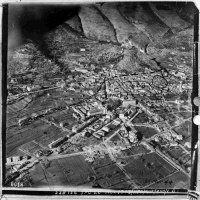

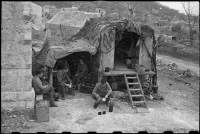

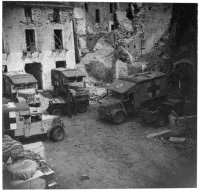

| The Italian campaign was a hard fought series of battles that was particularly taxing on the 2nd New Zealand Division (2NZDiv). The mountainous terrain and the climatic extremes meant that the Kiwi soldiers had to combat the elements and German defenders that were determined to hold the Italian peninsula and shut down the A llies southern thrust. They defended the many rivers that cut across Italy by defending canal systems and bridges, often destroying them as they retreated. The German units that fought in Italy were, like the kiwis, experienced and the campaign was not going to be easy. The Desert war was conducted in a theatre that was relatively devoid of civilian populations; the same was not true of the Liberation of Italy. The close proximity of Italian civilians and particularly female, meant that many Kiwi soldiers had the freedom to mix and develop relationships. To this end the New Zealand military and the Government faced the prospect of Kiwi soldiers wanting to marry and bring back to New Zealand their Italian Brides. Out of the bloody conflicts of the Second World War came a positive and romantic conclusion for many Kiwi soldiers who brought their Italian war brides home. Enlistment | Italy | First Action | Counter Intelligence | Bringing Home Italian War Brides EnlistmentPatrick: Stuart did you volunteer early?Stuart: I volunteered to go into the army and I was rejected on medical grounds. I was classified as grade three and I was very disappointed. So I was back in Civi Street, back doing my ordinary work. Luckily I was a member of the Masonic lodge and the man in charge of recruiting was a Captain Crutch and he was a member of the same lodge as I. I had a friendly association with him and so I eventually said to him “you know I would really like to get in the armed forces and go over seas” and he said “do you really want to go?” I said “oh yes I do”. And right and he passed me fit so I went into the army. At that stage, the Japanese forces were coming down through the pacific, they came right down and we were getting a bit apprehensive. The government mobilised what they call a home guard battalions. They wanted officers for the home guard battalion and I was commissioned as the 2nd lieutenant. I was named as the adjacent of the Wenawakura home guard battalion. As a temporary staff member. I was a regular solider and I had two others with me. We were responsible for defending an area from the Okehu stream just north of Wanganui up to another small stream just south of Hawera. I based my headquarters at Waverley. After the battle of Solomon’s in the coral sea, the Japanese threat receded somewhat, it wasn’t the same threat to New Zealand, so the home guard battalion was watered down a bit so they didn’t require the formations that they had. So I was transferred from the battalion into Linton camp where I was a quarter masters for a while but I resigned my commission so I could get overseas. I was put into the eleventh reinforcements as a private and then I was made a sergeant and then I was made a private again. By the time I got on the ship I was once again sergeant. I arrived in Italy with the eleventh reinforcement as a sergeant, 16 platoon, 25th battalion, 6th brigade, 2NZEF. Patrick: How would you describe the training that you received? Stuart: The training was basic infantry training and it was physical. you had to be physically good, so it was a lot of physical training, you know marching, marching out, marching over different country, staying out over night, crossing streams, we did a lot of training like that, we would go down to the rifle range and we would a bit of shooting, you are suppose to be able to shoot reasonably accurately, that’s about all we did. Patrick: Was there always plenty of ammunition and equipment available? Stuart: No, no that was limited, that was limited. By the time I was doing the training we were virtually finished with the dessert we were over into Italy that was a quite a different country all together. ItalyPatrick: What were you first impressions of Italy?Stuart: we went to Maadi military camp in Egypt, and did a little bit of dessert training there. I don’t know whether it was much good for us, it must have been more to get us up to a physical standard I suppose, because uh, there was nothing like the dessert in Italy. And then we went over on a ship called The Bartory. The ship Bartory was built in Poland; it was commandeered by the navy and used as a troop ship. We had a unit of Gerkers with us on the ship and they did most of the sentry duties on the ship itself. When we arrived in Italy, nobody knew we were coming. We went to base camp in southern Italy. When we arrived, they had no room for us. So the first night was spent out in the open on the ground. Don’t think of sunny Italy, it was of March and the ground was covered in snow. We scooped out the snow, and we slept in the ground the first night. So that’s an introduction to Italy. From base camp we were posted to various units, and I was posted to a sixteen platoon of D company of the 21st battalion, and that’s how I got to the battalion. Patrick: What was the morale like of the men, at the camp? Stuart: Oh Quite good, yeah quite good. Patrick: Was everyone was really anxious to get into the fray? Stuart: Yes, most of our reinforcements were very anxious. By the time I went overseas; all the people of the reinforcements were conscripted. There were people who had called up in their respective age groups. Patrick: How would you compare it to the patriotism back then to the patriotism today? Stuart: I don’t know I can’t compare it. Because you see in those days, there was the need. You know, the need for defending the country, it was very real. Now today, it’s all hypothetical. Isn’t it? Now I’m sure that if the need arose, New Zealand wouldn’t fail. Times produce the events, and events produce the men. Patrick: What was it like to be posted into a new platoon with a whole new group of men? Stuart: Well, um when I came to platoon, other men came with me. The platoon was made up of people who had been there for some time, people who had been through a fair number of actions, people who had never been in action and people who had just arrived. It was a mixed lot. A platoon is made up of 33 men. That’s 3 sections of 10 men each and each section has a corporal in charge and a lance corporal as a second in charge. It has 3 sections of 10 men each, that’s 30 men. Then it has a platoon headquarters which is an officer, platoon commander and a sergeant, and one what they call them, runner, a dog’s body. Does everything, runs here, takes messages here and does all sorts of things. That makes up 35 men we never went into action with 35 men. We were lucky if we had 25, we thought we were well equipped. That’s because men got killed, men got wounded and a certain number went on leave. Then in every action we had what they call L.O.B which, stands for Left Out of Battle. You always took 2 or 3 men, probably one from each section, 3, 4, 5, and they were kept out of the fighting. The theory being that if either the platoon got wiped out, you’ve still had the nucleus to form a new one. Patrick: If you were to be assigned your objective was to take a machine gun post, how would you go about it, what would you do, what would your company, I mean your platoon or section do in order to take out that out that particular objective, what would be the usual tactics used for this kind of assault? Stuart: Well, the normal tactic would be to the platoon. There three sections in a platoon, a normal section, a normal attack would be to have one in reserve, would have one to, for put down covering fire, and another one to do the attack. Usually, covering fire was somewhere in the frontal area. The actually attach would almost always be from a flank. And the reserve section would be to uh, come in and assist if anything extra was required, and to help occupy the position. Or, if they, one nest was taken and another one had to be taken, well then, that would be a fresh section to leap frog and attack the next one. That would be the normal ah method. Patrick: Once you got into the posted to your platoon, how were you accepted by the men that could be called “seasoned veterans”? Stuart: Oh no problem, no problems at all Patrick: And how would you describe the formalities involved? Stuart: Oh the interchange the formality the relationship was very loose and very casual. Patrick: Can you describe how Italy’s terrain and climate impacted on your ability to fight? Stuart: In the winter time it was bad news because it was cold and there was snow. The people who dominate the ground and occupy the high ground and the high ground must have found it very cold. Up in the mountains its cold, where it’s sunny down on the plains, down on the plains its easy going when their was no fighting. Cassino was warmest at the lowest level. Ahhh, that was Cassino, it was a wet muddy difficult operation. Patrick: What was your involvement in the Battle for Cassino? Stuart: I wasn’t involved in the New Zealand fighting for Cassino. I was involved immediately afterwards. We took up a position on the right flank under Mount Cairo and we occupied an area there. I remember we use to scoop snow out and find a place to bend down. We were very much under observation from Mount Cairo which is right alongside Monte Cassino but it was much higher mountain. When they bombed the monastery we were had a prime view from the eastern side. We looked across at the monastery and watch it dissolving in all this bombing. Patrick: Was it quite a phenomenal site, the bombing of the Monastery? Stuart: Oh there was a lot of smoke and you know after a few bombs had been dropped you don’t see anything but clouds of smoke and dust. Patrick: In your personal opinion, do you believe the Germans were using the Monastery as an observation post? Stuart: I think it’s fairly well established now that the Germans weren't using it as a defensive position. But at the time it looked as if they were because a lot of fire was coming from the direction of the monastery. Of course it was sitting on a hill like that and they had a lot of pits on the front of the monastery. We know now that he didn’t actually have troops in the monastery itself but we didn’t know at the time. Afterwards when there was all this hoo-hah about whether they could bomb the monastery or not, I said well as far as us as we troops were concerned the right thing was to bomb the monastery. it was a military objective and we were there and we were being shelled, and chaps were getting killed, chaps were getting wounded and you couldn’t ring up a member of the parliament and say what do you think, do you think we ought to bomb the monastery or not, you couldn’t do that. It was there and it had to be neutralised. First ActionPatrick: When was it that you first went into battle, or when you first faced with the job that you had been trained forStuart: Well I suppose it was on the right flank of the town Cassino. When I first went on the front line and we took over a sector from the Poles. The Poles withdrew and they regrouped and eventually it was a Polish division that neutralised Monte Cassino. When that was done, we regrouped and we fought, and when I say we fought us really chased the enemy up the valley. He had no defensive position up the valley until he did get the came to some high ground where he could ah entrench himself and cover the approaches of the enemy. Patrick: What your thoughts when you were preparing for that first time up at the front lines? How did you prepare yourself mentally? Stuart: I can’t remember, I think all we did was make sure we had ample ammunition, and made sure we had one or two grenades. I got rid of my rifle and bayonet and got a Tommy gun which always had a lot of bullets. If you kept your finger on the trigger all your bullets are gone in no time at all. I taped two magazines together, so that instead of replacing magazines, I would just take it out and turn it over and put the full one in with the empty one underneath. In addition I carried a little a box of .45 bullets to replace the magazines and they were heavy, you know I didn’t like carrying those, but I carried them because if you didn’t have anything to fire you were a dead duck weren’t you! Patrick: How did you make sure all your men were prepared or an attack? Were some more noticeably afraid than others? Stuart: I never thought of it like that, I suppose as a matter of course we kept out weapons in good order. Many times when I was out of the line, as well as preparing for an attack, I would take my Tommy gun into pieces and clean it throurely and make sure it was absolutely clean and wasn’t gonna fail me at the right moment. When the time came we had our orders we were told what to do and we were told how to do it and we just went a head and did it. Patrick: Was that where there any cases which you experienced or heard of that some men were over eager to get into battle? Stuart: I had a one member of the platoon who would often say to me “come on boss” he said “lets go and do a little bit of skirmishing” and I’d say “what do you want to go and do skirmishing for” oh he’d say “oh good fun doing a bit of skirmishing”. I never did any skirmishing. I was always there to do as a platoon sergeant and did what was arranged you know tactically and strategically by those in charge. To go off and do things on your own wasn’t really the thing to do; it wasn’t a personal war you know. Wars were fought and strategy was set out and you played your part in those. He eventually lost his leg to a piece of a roof tile. A mortal bomb fell on a roof of a house and shattered the tiles on the roof and one of the tiles damaged his leg and it had to be amputated. Patrick: He was the only one you knew of? Stuart: I don’t know if he was serious about it, no you wouldn’t go and do anything on your own like that. Patrick: Is there any sort of heroic moment that stands out? Anything of any heroic, heroic of yourself or the platoon? For members of your platoon? Stuart: Well each action we did do was a pretty horrendous and heroic affair. we had many actions you know so they might have been heroics but it was just one men went missing after another after another after another, so you know compared with civilian life they might have been enormous situations but in the run of things when you are in a war situation, its just one thing after another, no nothing stands out particularly. Patrick: I have heard and read that one of the biggest fears of a soldier was showing that fear in front of his comrades. Did you feel that in any way? Stuart: We were doing an attack just south of Florence. it was our job to secure the start line for taking the hill, we were the leading platoon leading up to this hill and we had to clear all the enemy resistance on the slope of the hill up to a certain line when the platoon behind us would come in and actually capture the hill itself. The thinking of that was that we were going to receive too many casualties on the way up to capturing the hill that we wouldn’t have enough strength for the final assault. We were going to clear the way up to a certain position and then the platoon behind us would come in and make the final assault on the hill. Unfortunately the commander of the platoon behind us which, was going to make the final assault was killed by an 88 millimetre shell. I was at the rear end of our platoon and he was leading his platoon right beside me when he was killed. I was wounded and when I came too I didn’t know where I was, I couldn’t find my gun, I couldn’t find my helmet, there was smoke and dust everywhere. I eventually located the platoon which had gone a little bit ahead of me. I stayed with this platoon for the attack, we captured the hill and I cleared the place for the platoon behind us to occupy. We were subsequently menaced by a Tiger Tank which came in behind us, luckily there was an anti tank gun which fixed the tiger tank for us otherwise we would have been in trouble. The next day I was in such bad condition, I couldn’t hold my Tommy gun. I couldn’t hold it, I couldn’t do anything. The officers said “your useless here Hayton. You really need to get out and get yourself attended to”. So I left the platoon and went to the regimental aid post. I remember lying out on the ground with the sun there with the smallest scratch on my little finger which had got hit by a piece of shell fragment, nothing else hurt but that little finger. Well eventually went to an English hospital in Rome and I went from there down to the second general hospital in Concerto. I was operated on there and had all sorts of bits of steel that dug out of me. I was decommissioned and posted to a counter intelligence unit. So I was put in charge of a counter intelligence unit. Incidentally, not so long ago I was having a chest x-ray and the doctor said well I have looked at the x-ray and there’s nothing wrong with your chest but you’ve still got a bullet in the back of your chest there, it was not a bullet but its a piece of shrapnel which I’ve carried there for all these years. Patrick: So your wounds were all from shrapnel? Stuart: There were bits of shrapnel all over me. I had them in my arm, I had them in my hands, I had them on my backside, I had them in my legs, I had them in my chest. It took several weeks to come right. But I stayed at the platoon for the attack I stayed at the platoon until we had a consolidated our position. I went out on patrol that night just to make sure there was nothing in front of us that we weren’t aware of anyone in front of us. By the end of that I had physically deteriorated so much I couldn’t hold a weapon at all. So I was useless as a soldier. There were a number of other New Zealanders at the British hospital in Rome. And we thought that the service was very poor so we complained and said we were going to go to our own hospital which was the 2nd New Zealand general hospital again located in Caserta just out of Naples. We went down there and we had very good treatment there, they fixed me up, doctors gave me a good examination. They said I needed an operation to take all the pieces of the shell out. So they operated and that was that. Patrick: How would you describe them in general terms, the success rate of the actions, attacks that you were in? Stuart: Well they were just attacks they were not all successful, I wasn’t in any attack that wasn’t successful. Ahh, when I say successful we exceeded our objectives. Sometimes it was costly, sometimes it was costly in men, sometimes it was costly in material, sometimes it was costly in wounded but every action I personally took part in we archived our objective. Patrick: How would you describe the noise in the battle? Stuart: Oh, the of noise in battle. You know when the gun fires, even when a rifle fires it’s a lot of noise it’s very hard on the hearing. I when I came to, I couldn’t hear anything, you know my hearing had gone, and I caught up with the platoon and I asked somebody a question and I couldn’t hear what they said. But we were young, we were fit and we were physically in good shape, and we recovered from experiences like that quite quickly. The most intense action would be the attack on Mount Lignano. Mount Lignano it was in the central part of Italy overlooking the key town of Leto, it was a communication centre. We captured the hill and unfortunately our own artillery which was trying to shell the retreating enemy failed to clear the crest and shelled us instead. Patrick: Was that an isolated incident or did it happen a bit? Stuart: It occurred more than once. The artillery use maps to try and describe the contour of the ground but they weren’t all accurate you know. Often the ground was different from what the map said it was, sometimes because of the shelling and bombing. So they were firing according to the map and when the ground was different the shells landed differently than intended. It is Terrifying. Terrifying whether it’s your artillery or his. Patrick: Did you ever deal with any seriously wounded men? Had you any basic first aid training? Stuart: Oh Yes. We came out of one action and I brought out a chap named Ted. I taking him down to the RAP and I can remember Ted lying across my knees like that, and he just died, and we couldn’t find anything wrong with him, we couldn’t find where the injury or anything was, he just died in my arms. Patrick: What may have been the cause of his death? Could it have been the concussion from the shelling? Stuart: I don’t know. It might have been it might have been a bullet, or probably something that had hit a vital organ of his. The entry point was so small we couldn’t find it, of course it was very casual, it wasn’t like in a hospital or an operating room, we were out on the field, in the dark and he was fully dressed in his uniform. Patrick: Was it; was it quite a peaceful passing? Stuart: Yes, he said he was in great pain and then he just closed his eyes and he died. Just like that Patrick: What were your initial reactions to that? Stuart: My initial reaction was that I left. I left him with the RAP. It’s their job to look after him, it’s their job to put him in the jeep, to take the body out and bury it. I just went back to the platoon. Patrick: So by that stage had you become, had you become hardened to the realities of war by this time? Stuart: I suppose. We weren’t greatly affected by it. Some chaps were but he wasn’t so close to me, he was one of the Bren gunners. I was sorry to have lost him, I liked him as a chap and he was a big person so he could handle a Bren gun well. It was a pity to lose him. I don’t know what I felt apart from that. Of course you see when you are an infant in a platoon you expect to have casualties, you know it’s a of part of our life in the platoon, if you are going into action you expect to have some casualties. Patrick: Were you ever given an order not to stop for the wounded during an attack? How do you feel about that kind of order? Stuart: That was standard practice, standard practice. You see if you were in the middle of an attack and every time someone was wounded and the soldiers stopped to look after him there would be no soldiers left to do the attack. So those other the few that were left there would be alienated wouldn’t they. No if a chap was wounded well then the best people to look after him were with the RAP [regimental aid post] and the Red Cross whose job it was to look after the wounded. No it wasn’t good policy to encourage your troops to stop for the wounded Counter IntelligencePatrick: Stuart, you said you were posted to counter Intelligence once you recovered from your wounds. What did that job entail?Stuart: I was the officer commanding Five New Zealand field security section and we were responsible for the security of the lines of communication from our base area to the divisional fighting area. It didn’t extend within the divisional fighting area they had a separate security field section for doing that. We were responsible for our lines of communication and of course eventually, those lines of communication extended from Maadi in Egypt all the way up to Trieste at the top of Italy. Now I didn’t do anything about the lines of communication between the Maadi and Italy because I didn’t think there was any danger to be had there, but I was responsible for my base camp which is down in Bari. In other words for the length and breath of Italy itself Patrick: Was it a difficult job? Can you describe some of your responsibilities? Stuart: No, no. there was a lot of field security sections I was with the only New Zealand section but the Americans had a lot of them. The Americans had a CICA unit and the British had a lot of field security sections and they worked in conjunction quit a bit. I sent my reports to one to headquarters in NZ and the others to GSIB that’s “General Staff Intelligence B Section” which was cantered in London. The British provided me with funds. If I wanted money for dealing with the civilian population they would give it to me. If I wanted say 60 000 lira, I’d say can I have 60 000 Lira and they would give it to me. I didn’t have to write a reason for it, all I had to do was ask for it and I would get it. And we used the civilian population; I used members of the civilian population in the ascertaining of civilian matters. At one stage, I had a three Italian motor commuter boats under my command on the Adriatic side. It was really easy for enemy agents or deserters to infiltrate behind enemy lines just by posing as fisherman and drifting down from the German lines to our lines and then coming ashore. I stopped all movement. Sometimes we wouldn’t let anybody go to sea and go fishing they didn’t like that at all. Of course it got so far ahead that the danger was virtually nonexistent. So I allowed them to go to sea and fish. And even asked permission to put on a special banquet for me. The people at this banquet treated me very very well. They gave me a fish meal, fish freshly garned from the Adriatic Sea, they skinned it for me in front of me and took all the bones out for me. They put it on my plate and said enjoy. Patrick: Did you ever have to deal with a black market or many cases of looting? Stuart: No, no I never came across any looting never came across any of that. I didn’t come across any looting as such. Although we were hold up in a house under full view of the enemy and we were short of water. And there was a well outside but to get to the well you had walk out in the open and in full view of the enemy. Well, I suppose looted could be used because I ram sacked the wardrobe and found some women’s clothing and I dressed up as a woman with a school dress and a head band on. I got a water container, put it on my head and walked out to the well in full view of the enemy and filled the thing with water then I walked back to the house. So we had a supply of water and I never got shot at! I suppose from a distance I looked like a woman. Well I suppose I did, did loot the clothing; yes I pinched it out of the wardrobe. Patrick: How would you describe the sorts of hardships that they had to deal with whilst the war was going on? Stuart: Ohh, everything was just destroyed; you know it was destroyed completely. I know that when we went up the valley the civilians were coming down out of the hills. Women carrying babies that had been born up in the hills. They had to leave the villages which were destroyed by shell fire, partly by New Zealand fire, partly by our Allies fire, and they had come down out of the hills where they’d been living because their homes which were blown to pieces. Ohh, they had a hard time. Patrick: How would you describe your responsibilities when dealing with the enemy? Stuart: Ahh no, I haven’t thought about it since. Our job was there we were soldiers; our job was to kill Germans. That was our job, so we were sent to work to do it. Patrick: In a nut shell, how would you describe the Kiwi soldier? Stuart: Ohh I think the Kiwi Soldier, number one he is not frightened by anything, number two he is very resourceful and number three he gets along well with civilian populations. He’s popular. Patrick: Do you think that the background of the man played a role in what kind of soldier they became? Was there a difference between a rural upbringing or urban upbringing? Stuart: No, no never thought anything about it, we weren’t great on to analysing what people were and what they thought or how they did things, you know we were just there as a platoon, we were trained to fight, we were told how to fight, we were told how to do the attack, we were told when to do the attack. We were told when to received orders, we carry them out, you know we didn’t really analyse it, we didn’t do any analytical thinking at allThe Germans, now they were really better soldiers. The best soldier, the best soldier in the war was a German soldier. He was undoubtedly, as a soldier you couldn’t better them. We beat them because we had more resources, we had more industrial resources. We had more men. We were able to assemble a greater preponderance of fire power and all resources were walled at the enemy. Patrick: How did you see these resources being assembled? Do you mean the world collectively acquired the resources to beat the German Military? Stuart: Oh well we couldn’t lose, see once America came into the war, you couldn’t lose, see America have got enormous industrial potential, now it produce aeroplanes it can produce military ships, it can produce tanks, it can produce more and men too, you know, two New Zealand ahh two and half million people, America 285million people, you know enormous resources, America was remote with nobody bombing their cities, nobody interrupting their production, you know you cant win against that. Germany was 60, 70 million people and they had large production too, but they had they had suffered a lot of damage, even if only a last part of the war was fought on their territory but they had from bombing and a result of war action they suffered tremendously. Bringing Home Italian War BridesPatrick: Can you tell me about the job you were given once the war ended?Stuart: When the war was over I gave a half ton truck to each man in my unit and a movement order telling them to take 7 days leave and go where they liked in Italy. All they had to do was to bring the truck back in one piece which, they all did. I travelled around a bit myself and then when I handed all my gear and equipment in I was posted as a staff officer to headquarters 2NZEF, at that stage was stationed in Florence. A number of officers and I took over the hotel just around the corner from the railway stationed. We commandeered that and lived there for about 6 months and so I was a staff officer. At the headquarters of the New Zealand Expeditionary force there was a pile of applications from New Zealand soldiers to marry foreign women. during the war and rightly so too, those in command said that soldiers weren’t there to marry women they were to fight a war, and so nothing was done about them and no decision was made but when the war was over somebody said well we better deal with all these applications. And I suppose somebody must have said “there is Hayton not doing anything so give him the job”. So they gave me the job and handed me this pile of applications and I became in charge of foreign marriages. And what did I do? I first of all I had consultations with the legal people in Italy to ensure what was the legal position for a valid marriage in Italy because a marriage that is good in one country is usually held to be good by other countries. In Italy you can be married in a state office or you can be married in a church. If you are married in a church, you’ve got to have your marriage registered in the state office and it’s got to be registered in the state office of the same locality as the church where you were married. What happened in some cases, New Zealander soldiers got themselves married in a church and they were told they were married in the sight of God and to go out and enjoy it. then they would come to me and say to me ‘we are married’ and I would ask it they had the marriage registered and they said no we haven’t and so I had to go back and get their marriage registered in the place where they married in the church. There weren’t very many that were forced to be married traditionally but they couldn’t get married unless I gave them permission. That didn’t say that some people didn’t get married without my permission some people did but generally I investigated most of them and gave authority for all to be married except one. Some of them didn’t marry in Italy some of them came decided to come and get married in New Zealand but eventually after while I decided that if I didn’t do something about this I would never get home myself. I went to the war married with two sons and it was time I got back to look after my family. So I set up a base in Bardi, got a building there and I got a touring bus, a 3-tonne truck and a staff car for myself and went up to Trieste where I started by picking up the approved wives in Trieste, and I drove down through Italy, picking up wives all the way down. I eventually arrived back in Bardi when in this building I had a depot and a sergeant major. I had a few helpers including some German prisons of war that I used as servants assembled there. Then I sent a signal to the headquarters 2NZEF in London asking for passages for these wives to get to New Zealand. they replied by saying that they wouldn’t provide them with a place on a ship, they said our job is to get soldiers back to New Zealand not to get the Italian wives to New Zealand. So next time I sent a signal I just asked for a so many places on a ship didn’t say who they were for. And they gave me so many places on the ship and when the came ship to Bardi from Torrento I put all the wives on board, put myself on board and we came back to New Zealand. When I came back to New Zealand oh I looked after them to some extent on the ship too, we had a few problems but not to worry. I handed them over to whoever was the authority and I had nothing more to do with him after that. On the wharf was my wife, my mother and my father and my civilian life started. My army life had ended but I did have a relationship with one of the Italian wives who married a boy who was in business in New Plymouth and she lived in New Plymouth so I saw her from time to time. Patrick: Can you say there were problems on the ship, what sort of problems were you faced with? Stuart: The two main problem was that the wives that had their fiancé on the same boat were shacking up with each other and as they were pretty close. In the cabin there were several others and they used to complain about it. The other thing was that they stuffed up the sanitation system with sanitary pads they would bung down the toilet blocking them and the sanitary system wouldn’t work. Ahh it was an awful mess because with a boat full of people you must have good sanitary system, yeah so we had a few problems there I had to talk to them pretty straight about that. Patrick: How did you deal with having to fit back into Society once you were discharged from the army? Stuart: When I got back to civilian life I had a wife and I had two children and they didn’t know who I was and I had to re-establish myself. I had to find another house, my wife had run out to the family farm where she lived during the war and I had to find a home for our family. I had to re-establish myself and all these sorts of things kept me kept me pretty busy I didn’t have any sad things or any thoughts about the war or anything like that. I went along to the RSA and asked I said to them what can I do with to help with the service men, they said well there are a lot of chaps ending up in hospital and we want someone to look after hospital visiting so I did that I did it for 50 years, I gave it up when my hearing disappeared and I couldn’t really hear what people were talking about. And those few years after the war must have impacted on interfamily relationships of a lot of men that went overseas leaving behind their wife and young children. Patrick: How do you feel about your experience of war and military life, do you think that it contributed to your life after the war? Stuart: Yes I do, I think the fact that I think that the fact that men that went overseas and fought for their country gave them a certain mana, a certain standing in the community whatever the position they occupied, you know they were soldiers who had fought for their country, they should to be admired hadn’t they? War is a terrible thing, and I wouldn’t advise anybody to undertake war light heartedly, to fight is a radical instinct and we shouldn’t fight, but there are certain things that are worth fighting for, there are certain things that you mustn’t give up and if they are threatened you got to defend them, there is no doubt about that. |