It's Not Always Easy

| Charlie Reed was a territorial soldier prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. With the German invasion of Poland Charlie signed on with the 2nd New Zealand Division (2NZDiv) as an artilleryman, leaving for war with the First Echelon. Charlie found that war itself dictated the intensity of the conflict and not the soldier, and despite partaking in some of the major engagements of the war; he was left with the feeling that he had not fulfilled his duty. | |

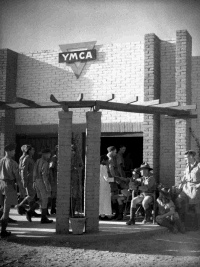

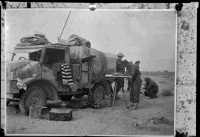

![Relief of Tobruk. Join up of 8th Army and Tobruk garrison, 27 November, 1941. Lieutenant-Colonel S F Hartnell is on the left. British official photograph. Notes on back of file print include 'Prob 19 NZ Bn [?] at Ed Duda. NZ Officer - Lt/Col S F Hartnell. Tobruk - Link up - 2 Libyan Campaign. 19 NZ Bn - Ed Duda. 32 Army Tank Bde - Ed Duda.' Relief of Tobruk. Join up of 8th Army and Tobruk garrison, 27 November, 1941. Lieutenant-Colonel S F Hartnell is on the left. British official photograph. Notes on back of file print include 'Prob 19 NZ Bn [?] at Ed Duda. NZ Officer - Lt/Col S F Hartnell. Tobruk - Link up - 2 Libyan Campaign. 19 NZ Bn - Ed Duda. 32 Army Tank Bde - Ed Duda.'](https://www.kiwiveterans.co.nz/images/custom/interviews/its_not_always_easy/thmb/relief_of_tobruk._join_up_of_8th_army_and_tobruk_garrison_27_november_1941._da01658f.jpg)                   | Artillery had its beginnings during the New Zealand Land Wars. By the early nineteen hundreds the quality of guns were improved and 18-pounders and 4.5-inch Howitzers were employed by three Kiwi batteries at Gallipoli and on the Western front during the First World War. By the outbreak of the Second World War, these guns had been replaced by the 25-pounder with three regiments of three batteries (seventy-two guns) supporting the 2 New Zealand Division. The usual image of the African campaign is of Rommel and Montgomery attacking and counter-attacking with fast moving tank divisions, but the artillery was ever present and just as important. As part of the Eighth Army, the NZ Artillery shared in the mixed fortunes of the desert war. The dual anti-tank and artillery support roles made the guns vulnerable to tank attack, because of problems arising with the need to site the guns well forward, while also having to engage enemy tank formations when supporting infantry as seen during the Crusader Offensive of 1941. Despite these setbacks the New Zealand artillery was a vital part in the Allied war effort in North Africa, providing anti-tank support and field artillery capabilities, culminating in the battle for El Alamein where a massive 900+ guns supported Monty’s Eighth Army. | To Egypt | Greece | North Africa: Lucky Escape No.2 | Alemein | Italy: Bit by Bit | To EgyptPatrick: Can you please describe leaving New Zealand for Egypt? Did you make many stops on the way?Charlie: I went away with the First Echelon. As a gunner, that’s a Private Soldier, in what was called the Fourth Field Regiment. We trained at Ngaruawahia, the camp was known as Hopouhopu. We sailed from Wellington, we had one leave over Christmas, 1939, and we were back into camp. About the 2nd of January, we came down from Ngaruawahia by train and embarked on a ship, the Empress of Canada, which was a British Liner. Away we went with the rest of the First Echelon. We went off with an escort of one or two or more naval vessels, and we sailed to Sydney. There we had General Freyburg on the boat with us and he got off there, with one or two other people. “Tiny” [General Freyburgs nickname] flew on, we didn’t know where he had gone, he just flew off. There was an advance party that had left in December; we didn’t know where they were or who they were. It was all highly secretive. We sailed around the Australian Bite to Hobart. We were there for a few days, before we sailed on; we were very, very well treated by the Aussies in Perth. Eventually, when the Aussie contingent was all assembled, we sailed off heading for Bombay. We spent a few days there, had quite a bit of leave in Bombay so we had a good look around. And away we went up through the Red Sea to Egypt. Patrick: Once in Egypt, where did you set up camp, was it strictly Military Personal? Charlie: There was a camp at Maadi for British troops. But they were in closer to the actual Maadi Village which was really a suburb of Cairo, and it was really seen to be more or less used by British people. There were an awful lot of British troops established there, they had been there for quite some time. On top of that there were an awful lot of just ordinary people just working for the British Ambassador doing all sorts of jobs. There were a tremendous lot of them. Actually, I got to know a woman working there very well, a New Zealander; she had been in Cairo ever since WWI. She had been a nurse for the British troops and NZ troops when they were in Egypt. She stayed there and ran a sort of boarding house? I don’t think they called it a boarding house; it had some high-faluting name. She had a tremendous connection with an awful lot of English people, even people coming out to serve in Egypt and they rushed around to her place very quickly. It was quite a fun place to go to. The Naffies [MPs] tried to keep it in order. Patrick: Did it take long to establish the New Zealand section of Maadi Camp? Charlie: A lot of it was tented, but they had some other buildings up already. I can’t tell you just what were built by the time we got there but they weren’t all buildings. We ended up with a big theatre where we used to go for films and other functions. There were an awful lot of buildings for messes, where you go and get a certain amount of feed and drink, it was like a tavern. They had them for the officers, they had them for the Sergeants Mess. I had a stripe so could get into some of these places. Patrick: When were you commissioned, what did you have to do to get a commission?Charlie: they wanted more officers and so they sent off for so many recommendations from every unit that they wanted to, well every unit I think got the chance to nominate people. The actual Officer Training Cadet course that I went to, had troops come from everywhere, the Artillery, the Infantry, the Machine Gunners, the various units’ right through to the … RMT, that was the Motor Transport, they came from everywhere. We were all trained more or less the same, we weren’t trained in our specialty, we were just trained as infantry really. We were lectured an awful lot. I played more sport when I was there than any other time of my service. I played nearly everything from Rugby to Cricket to Tennis. I don’t think I played golf but you know I had a good time. Greece: Mediterranean GamblePatrick: The divisions real first taste of Combat came in Greece, can you tell me about your involvement in the Greece Campaign?Charlie: The Greek Campaign was a proper disaster because there weren’t enough troops in Egypt to send away and stop anything. Trouble did occur. Before when we were first sent there, the Italians started to come down into Greece, and attack them... but they didn’t get on very well, and the Greeks held them pretty well but not quite enough. They were afraid of what would happen if Germany came into the fray. well in due course that’s what did happen, and we were there but we didn’t have enough forces. I can’t tell you exactly what we did have, but I know there were some Aussies there. We had quite a bit of support in the way of heavy guns from the British, but not nearly enough, it was only token. When the Germans came down, they had a complete hold on us. They had damn good pilots and far better planes than we did and they just over tramped us altogether. Now we hardly even saw one of our planes, and most of them were wiped out before we had started military operations, it all happened in a few days. Patrick: When was the first time you got to fire your guns, in anger? Charlie: In the first two positions we went to, that is my troops, we didn’t fire a shot and that was because we were a link troop and we didn’t get instructions to fire. That was at Mt Olympus. Then at the other pass they moved us to before we saw a gun fired in anger. Patrick: Were you anxious to get out there and take part in the shooting? How did the artillery perform? Charlie: Well, it’s bloody awful being there without doing anything. At the 2nd pass we had our guns in operation and we were shelled a bit, but no one asked us to fire a round, we just sat there and did nothing. But when we got the order to move, we retreated and came way down out of the mountains and out along the coast and into Greece, we did start shooting. It was all very unskilled. We hadn’t been trained enough. Our Officers weren’t properly trained, how the hell could they be? Some of them were brilliant in World War I but this time it was whole different ball game, and they hadn’t been trained for that at all. The same thing happened with the Junior Troops, they weren’t trained for that kind of war, and they hadn’t had enough training!I remember reading in a book that an authority from WWI said “it took three years to make a gunner”. That’s not necessarily the fellow who loads the gun and pulls the trigger, but it’s the trained people that work out the range, angle of sight and all that sort of thing. In those days, you see we didn’t have computers; and it was all done with logarithms. They were tables that surveyors used all the time. And we had to use them to get the line, in other words, the bearing, which you fired from your position to where you wanted to hit the target. Things happen you see when you are at one height and the targets down below you or way up above you, and that affects what’s called the angle of sight. My role was what was called a Specialist. This was before I was an Officer you see. I did this log work. Patrick: Once you became an officer, what were your responsibilities? Charlie: I was in charge of a Section of two guns, and I was the Left Section Commander, and the Right Section Commander had the other two. There were two Officers. Then there was another officer, it was the GPMO (the Gun Position Officer), and he was responsible for the actual firing not the directing of the shooting, cause that was all done further back, but he was responsible for the gun position and the instructions going out to the gunners as to what the line, range and angle of sight were. Patrick: How did it feel once you started to fire your guns? Charlie: Yes, but there was one business when we were in a gun position and suddenly I got orders and a vehicle came round, picked me up, and took me way the hell up to an Infantry Battalion Head Quarters as a Liaison Officer, but I had not telephone back to the guns and I had no wireless and I had nothing and I was just sitting there like a loo, that was the way things sort of happened. It’s a bit like things that happen in modern warfare, you see, like now, it happened all the way through World War II. Either the Air force would make a blue (mistake), or someone made a blue, and they bombed our troops instead of the enemy. It happens, no question about it. And the same thing could happen quite easily with shelling, unless you’ve got a pretty high standard of training and everyone is right on the ball, one gun or the whole lot can be firing quite in the wrong direction from where they should be. And at other times I’ve seen it happen, one gun suddenly it wasn’t, something in the mechanism of the gun went wrong, and the gun is just dropping down slowly, and suddenly we’re seeing our own shells landing just a few hundred meters in front of us. And the Huns were nowhere near that, they were miles away. Patrick: What did you think of the guns you did have at that point? Charlie: The guns we thought were jolly good and they were still the basic field gun at the end of the war. We didn’t have them to train on, we were still training on the old things that they had in World War I. When we got to Egypt we got issued with these 25 pounders and they served us very very well right through the war. But they had to be properly looked after and serviced with the proper instruction given to the gunner or they weren’t much good. Patrick: Can you tell me about your experiences during the retreat and eventual evacuation from Greece? Charlie: Well, I got lost. We had been coming down step by step down back to Athens, and we were given instructions to lie up in day light. This was because the German planes were just swooping down, and the traffic moving on the road was getting bombed and machine gunned; the casualties were pretty heavy. So we were instructed to where we could hide up in the trees and camouflage ourselves as best we could and do the next trip the next night. We were using quads which were vehicles that towed a trailer and a gun or else two trailers full of ammunition. The quad I was on had men from other units lying all over the roof; we had them stacked up where ever there was room. They managed to get a ride with another vehicle and I was down to just 13 men. We got down to Athens and by that stage the instructions had been to the Provo (military police) to direct us to cross the Corinth Canal but all the rest hadn’t crossed the Canal, they had got through to Athens.We eventually got right down to Kalamata in the southern part of Greece. There were quite a few other New Zealanders there and all sorts of other people that had been directed down there. But there was no way of getting us out. The first night we were down there, we assembled down at the beach to be taken out by the Navy. Evidently it was commanded by a New Zealander, one of the Herrick’s from Hawkes Bay. Anyway, he came in with his two vessels and he took off as many as he could and said “right ho, I’ll be back tomorrow night for some more.” During that afternoon the Huns came down into the village and captured the jetty where the boats were loaded and unloaded. that afternoon there was a big squall and one New Zealander, Jack Hinton, won a VC because they drove the Germans off the jetty and out of the village and we owned the whole thing again. That particular night the Navy didn’t come. I only found out much later on that the problem was the Naval Liaison Officer who had the wireless connection with the ships had been captured and his wireless and so the Navy hadn’t got a show, they didn’t know what had happened because they had no liaison with the people on the island. So, anyhow, to cut a long story short, my blokes had captured a fishing boat, and all the ones that were manning it were captured by the Germans that afternoon and whisked away, but we knew where the vessel was. So we took our quad and all the rations we had aboard, and we drove round through the village on to an embankment where there were rows and rows of Greek fishing boats tied up. We couldn’t get the truck down there we could only get it to the head of the wharf; we carted the first load down and chucked it into the boat. It was dawn and just as we had finished with this first load the Huns appeared in the village square! So we dived into the boat and hid. We were there all day and the Huns were that close that we could hear them talking. We were listening to them talking and could hear their boots as they walked past. They didn’t inspect every boat luckily. That night, one of our blokes picked up a rowing boat and he and another chap towed us out into the open water and away we went. But all the sails and ropes were all rotten and ever if a good hefty breeze blew up everything collapsed and just fell down. It had a diesel engine in it but although I had a diesel engineer, or he’d been trained as a diesel engineer, with me just by a fluke, he couldn’t get it to go! So we just sailed by guess and by God out into the open water. I had a compass, and the ship had a compass and so we just poked our nose in the direction of Crete and hoped for the best. And strangely enough we hit Crete! But the aggravating thing was that the Cretan fishermen who came aboard and helped us ashore had the blasted diesel motor going within 10 minutes! However, by that time, a signal had been sent to the HQ away on the other side of Crete from we were, and a vehicle was sent over for us to cart us back. When I was paraded in front of the Generals Head Quarters, he said “Well it’s not much good us staying there cause our regiment had gone back to Egypt.” What had happened was they had been on a vessel coming to Crete when they were caught by a German plane and a very near miss with a bomb damaged it so much that the Authorities said “Egypt”, and they sailed for Alexandria. They couldn’t do much with it you see. They couldn’t use it to try and dodge the planes when they were attacked, and they had no way of returning the German fire, they couldn’t do a damn thing. So I was pushed onto the first vessel going from Crete back to Egypt, and I went back and joined my own regiment. That was probably a very lucky thing for me because a few days after I’d left Crete, the Huns came in with their paratroopers. North Africa: Lucky Escape No.2Patrick: What happened once you hit Alexandria?Charlie: It was just a question of being put on a train and taken back to my particular troop. My regiment wasn’t at Mardi then. It was at another village further out, called Helboa, a bit further up the Nile. So I joined them there, and eventually we started just training again for the next battle. Patrick: Did it take long to sort yourselves out? What was the Divisions next move? Charlie: We were sent off up to the Turkish border. Yes, I’m sure that was the chain of events. Memory might be wrong but I think we were ordered up way up past Damascus and right up onto the Turkish border and we were there for a while. Then Rommel came to North Africa with some high quality German troops with him, and they started to do what to with what was left in the way of the British troops in North Africa. So we were, SOS’d for and back we came in a mad race right down through Israel, down through Cairo and straight on up the desert. So we were back in action fairly smartly. But, we didn’t really get on properly there either because that’s where I think it was at that stage that I got wounded. Patrick: You were wounded. Can you tell me what happened? Charlie: What happened? What really happened was that we were over run by the German tanks! My memory is a bit hazy as to the name of this place but I can certainly remember what happened. Our battery and all my guns were put out of action. I don’t know that every gunner was killed, but most of them were. The tanks came in and were firing consistently easily putting the guns out of action. They were just steaming along in their tanks supported by the Infantry. We could see them running behind them. I don’t quite know how close they were by the time we got out of it, but they weren’t very far away. When the final gun was knocked out, I was wounded in several places but they weren’t very serious. I mean I had a bullet through my arm, just above the elbow, I was very lucky with that one. One of my Sergeants and I were busy trying to drag this wounded man over to the shelter of an escarpment and when I got hit I was useless. I couldn’t use it and I couldn’t help. The only thing that my Sergeant said was “I don’t think it matters Sir because that fellow had had it anyway”. He evidently was very badly wounded, and would have died there anyway. Before that I had only just got these bits of ricochet, and didn’t really know I was wounded at all. I had one in my stomach; I think it probably was just a ricochet, as it was just sitting in the muscle in my tummy. Then I was taken with an RA team, to the RAP (Regimental Aid Post).Patrick: How were you received by the medics at the RAP? Were you taken out of action by these wounds?Charlie: The doctor at the First Aid outfit bandaged me up and he said, “Now don’t go away because we have to evacuate you.” With that, one of my gunners and one of the Officers in the battery came up the wadi looking for me. And they said, “Come on we’ve got the regimental doctor, our own doctor, with his vehicle and his red cross just down at the bottom of the wadi and he’s waiting to pick you up.” So they got me down there and chucked me on the back of the waiting truck and the officer went back down underneath the escarpment he must have been very badly wounded because he died the next day. As I was chucked on the truck, this gunner raced round to climb on the running board. But the RAP truck hadn’t detached its camouflage net and it was just dragging in the ground, as he trod on that he was just sent head over heels and no one knew what had happened to him. The driver and the doctor didn’t know and we didn’t know, all of us just dived onto back, and away we went. He was taken prisoner within a few minutes of that, but then he managed to escape before they got him away to Italy, and he came back to us and served for the rest of the time I was with the Regiment. Once we got out of the shelter of the escarpment, the Huns were sitting up on another escarpment and they were firing at us and that’s when I got the worst wound. I got a bullet that went down into the side of my neck and just missed my spine and came out leaving a dirty big hole in my shoulder. It took a good bit of my left shoulder away. Patrick: Was it quite a demoralising sight to see all your guns being destroyed? Charlie: Yes it is, very much so. It was quite interesting that a few days afterwards, the Huns were beaten back, and a British gunner moved onto that particular site and saw all the bodies and the guns and the mess and he picked up a rammer. It rams the shell, see, you put the shell in and the rammer fellow puts the rammer up the bridge of the gun and pushes the thing tight in and then they put the charge in. And so the rammer was picked up and I think it was engraved. The British officer was so impressed with this shimozle that he got this rammer and somehow it was down as one of my gunners’ rammers, just how they worked that out I don’t know. Patrick: Who took it? What was done with it? Charlie: He engraved and handed it over to the commander of the New Zealand Artillery, Brigadier Weir. Patrick: Excuse the dumb question; is it possible for you to describe what it feels like to be shot? How much pain were you in? Charlie: Well, it’s something I always wondered about, because you heard of men getting shot and screaming in agony. My reaction is that it had just felt as if someone had thrown a hunk of mud at me with a stone in the middle. There was no absolute agony about it. I was carried on into Tobruk and into hospital without really thinking that I was so frightfully wounded or suffering any great pain. I didn’t like the hospital in Tobruk much because the Hun was bombing it every night and the place was alive with explosives and search lights and the noise was deafening. When you were just lying in bed and can’t do anything, it’s not very funny. Patrick: How long did you stay in hospital for? Charlie: Not very long. We were transported into a British Red Cross Ship that had come to Tobruk to pick up casualties. They were rather marvellous. It’s rather funny, earlier in the war they had come out to Wellington, just after Greece, and brought those casualties home. The nurses told me they’d had wonderful time in New Zealand. They were just absolutely wonderful and they couldn’t do enough for us. We had a very pleasant trip from Tobruk to Alexandria. We were lucky that the Huns never attacked us, or chase us. We got down quite safely. AlemeinPatrick: Can you please tell me about your experience of the Battle at Alamein?Charlie: By the time Alimein came, I was an OP (Observation Post) officer. The night of the first attack, we went forward with the second wave of Infantry. By the morning we were looking for targets to direct our guns on to. Well, it was practically hopeless; I couldn’t find any blasted Huns. At one stage I was in an old gun emplacement, and a shell hit the outside of it, obviously fired by someone who knew exactly that the gun position was occupied. Patrick: Were you involved in directing the Artillery Barrage? Charlie: Yes our guns were firing barrages, yes very definitely. That’s what they were doing, but the point was that if the attack was successful and we drove the enemy back, inevitably the guns had to be shipped forward and the OP officers had to be up front to direct the fire power. Patrick: Were you right up the front lines moving with the Infantry? Charlie: I don’t think I ever caught up with it. In the night yes, but once daybreak came, I couldn’t get up there. I do remember on the second or third day of Alamein. I was on a ridge and waiting for daylight and trying to get our guns to fire smoke or something so that I could see where my shells would land, but there was such a bloody shambles of smoke and dust and everything else. All of a sudden we started to get shelled on this ridge and it got worse and worse and worse. I was crouched in this bloody shell hole and I woke up eventually to the fact the shelling had stopped. What was happening was one of our own tanks had came up and had its gun straight over the top of my hole and every time it fired I got all the lashings and the repercussion from the gun. Patrick: How long did it take for them to work out you were there? Charlie: I don’t think they ever did. Once they stopped firing I woke up to the fact that there was no enemy shelling going on and it was just this bloody tank, there was nothing I could do about it. Patrick: So what happened from then, did you get out of it? Charlie: The whole point was I still stayed up there because I was still trying desperately to see something and to get some fire up if it was needed. You know, things can be a bit confusing in circumstances like that. Patrick: During the battle, did you call in many enemy targets? Charlie: No, I was pretty bloody hopeless but I never got a chance to do what I was trying to do at all! Patrick: Did you feel like you hadn’t completed your objective properly? Charlie: I felt that I wasn’t earning my money and doing what I should do. Patrick: That was no fault of yours though … Charlie: No. That’s quite true, but the fact was that no way was I getting very much in the way of instructions back to my gun to do what I was hoping to do. Patrick: What eventually happened, from your observational point? Did the battle die down and you move forward? Charlie: Usually what happened in a situation like that was that the enemy were getting pushed back and then you up sticks and, well you went after them. You had to catch up with them to do any good and you only did if they turned around and tried to stop you. Patrick: Did the Germans carry out their retreat quite successfully? Charlie: You see, very often, in your particular area of the front, someone up here has pushed them back behind them and they were starting to get around behind them in a loop attack, we were in those quite often. With the 8th Army, the New Zealand Division was trying to get around behind them and cut them off and stop the main lot getting away. And once they, the Hun realised that we were there and coming, they bolted up the actual Mediterranean road. In this part of Africa was one tar sealed road that went more or less along the coast, and that was how the bulk of the supplies, food, ammunition, reinforcements, all that sort of thing, travelled. In some parts of the desert, the travelling was pretty good; they could do it quite easily. But every now and then you were in trouble, because you were in stuff you just couldn’t get out of, you just got stuck and you had to get hauled out. Wasn’t much fun. Patrick: Was it quite a hard job pursuing them? Charlie: Yeah, yes of course it was, of course it was and then some. Patrick: Did you end up capturing many of them as they? Charlie: Well eventually, in the final analysis, the Germans evacuated from Africa back to Italy, but they did not take very many with them, you see we captured most of the survivors. The Americans had come in from the other end, so they were getting caught between the Americans coming down from the other side of Africa, up near Algeria, and we were coming up through Libya. So the Huns had it. Italy: Bit by BitPatrick: So what happened after Alamein for you? Did you sail with the division to Italy?Charlie: We just went right on up the coast until the war in Africa ended, and then we turned round and came right back to Cairo. We probably went to Maadi camp. Anyway, they announced the furlough back to NZ. I think it was done on a ballot system. But eventually it got round the fact that everybody came home. I didn’t want to come home. I would rather stay and see the bloody thing out. So I refused furlong, and I went to Italy with the rest of the NZ division. But I wasn’t there very long, before I just got sent home. I was in an OP in Italy and the Battery Commander rang me up and said “You better dig yourself a dirty big hole boy, cause you’re going home tomorrow.” That afternoon the Huns started to range on to a big house behind me on a ridge, the one I was in was further forward and looked out over a fairly wide range of country. When the Hun started to firing all sorts were landing right along side my house, which wasn’t very funny. Patrick: How many men did you have with you? Charlie: I had my telephonist and a few other people with me, so that my orders got back to the guns, but I got instructions to go down to the Battalion for a conference. And when I got down there, the Commander of the Battalion said “You had better stay here Charlie, if you’re going home tomorrow you’d better not go back up there now.” I said “Well I can’t, because the officer taking over from me is coming up to relieve me, and I can’t run off now and leave him to sort of find everything without my being here, so I gotta go back.” That night I eventually was in my own vehicle going back and we had a dirty great big gorge with a very narrow road on the other side to get up, and one of our own tank regiments was coming in, and we got pushed off the road about three times, which was a bit nerve racking. We finally got back to Battery Headquarters and the Battery Commander and the Battery Captain were snuggled up in bed with a beautiful fire going and the boss said “ha ha ha” he said “you’re not going after all.” However, I did stay for another few days, but eventually the orders came and I was off. Patrick: Are you able to tell me about some of the actions you were engaged in while in Italy? Charlie: I started off in Italy, right down at the southern end. By the time I got back after furlong, the New Zealand division had moved from the Adriatic Coast where they were when I was with them, they had moved over to Casino, had fought their way slowly up, past Rome. they were right on the outskirts of Florence, and then no sooner had I joined them and an American Division took over from us outside Florence, and we went back over to the other side of the Adriatic coast. Patrick: Charlie, when you came home on furlong, were you involved with any of the protests about having to go back? Charlie: A lot of us went back. On the ship that I came back on from Wellington, were a lot of people who had come back from the Pacific, and they were being now sent forward as reinforcements to help the Division because they were short of men. Then there were a lot of people who hadn’t refused to go back, and they’d had their Furlong and were going back. Patrick: Are you able to describe to me your experiences of the actions you were involved in? Charlie: We had to battle, bit by bit. We fought our way up right up as far as the Senio and there the Huns made a pretty determined stand. It was a good sort of a river to hold up the British Advance, a good barrier. It took us a long time to build up our forces and get ourselves over the Senio, and push the Huns back up to the next river. All those rivers came out down and across the plains and out into the Adriatic. They were all quite good as barriers, because the Huns in most cases had blown the bridges. We had to get across the river and kick them out, so the engineers could build the bridges to get the main army through, we couldn’t get our guns across unless we had a bridge. So it wasn’t easy. Towards the end there I received orders about smoking out some Germans from some village “You won’t do any good down here, you’re wasting your time and the only chance you have of getting your guns down to Trieste is down the inside way.” I went down there with guns still ready for action. I turned the whole of the regiment, I don’t knowhow much I turned on but I turned on a good downpour of fire on that village and in the end there all hell broke lose on the wireless. There was the General who was down in Trieste himself and he was saying “Stop firing! Stop firing!” so immediately that overruled my instructions and I stopped firing! Patrick: Why did you have to stop firing? Charlie: He was busy arranging the surrender with the Germans in Trieste, he was down there dealing with that, and I was setting off thunder with my guns going off, they were trying to organise their surrender. Even then, things were pretty touchy, because at that stage, Tito’s men were coming in from the other side you see, and they wanted Trieste. They wanted to kick us out and take over Trieste from the Italians. There were some very touchy situations where we thought there might be some trouble at any moment, but eventually they managed to turn him back and get him to withdraw a bit further away through what was a long business of haggling by the Allies to get Trieste safely into their own hands. Patrick: What can you tell me about your encounters with the Germans and what you thought of them as a people? Charlie: I ended up right through the war having a very, very high opinion of the German forces, the soldiers, their equipment, their training and everything else. You couldn’t help admiring their Army. They were tough. Patrick: How do you remember your contribution to New Zealand’s war effort? Charlie: I’ve always felt that there were some times when I was proud of what I did, and there were a lot of times when I thought I could have done better. It’s not always easy |